The Queer Potential of Jennifer’s Body

In September 2009, Jennifer’s Body, directed by Karyn Kusama and written by Diablo Cody, premiered and tanked at the American box office. The feminist-dark-comedy-horror hybrid centers around Jennifer Check—a man-eating demon—and Anita “Needy” Lesnicki—Jennifer’s best friend. Much of the scholarship produced in response to the film explores the themes of the female body, desire, and sexuality but ignores the movie’s queer potential. I argue that examining previous critical thought in combination with fundamental theories on women in horror can help us understand the queer nature of Jennifer and Needy’s relationship and highlight what sapphic relationships in horror can look like.

Jennifer’s Body was a box office “flop” upon its release in 2009 (Deng, 1). Many involved with the making of the film claim it was mismarketed: it did not promote itself as a meditation of the pressures teenage girls face, but rather as a movie where its two leads would look hot, get naked, and kiss. In 2020, reflecting on the film’s premiere, Derek Deng writes it was advertised as a “straight male’s fantasy—nothing more, nothing less…viewers were already predisposed to critique the film through the lens of sexualization and objectification” (Deng, 1). The movie never stood a chance against the primarily male teen audience that attended its opening. It was not until ten years later that Jennifer’s Body reached its intended viewership. In 2018, Sarah Fonseca wrote about the development of the story’s cult following, stating: “Jennifer did find a slim but devoted audience to enjoy its ritual bloodlettings…And that audience is rife with queer women” (Fonseca, 2018). Jennifer’s Body has gained attention in light of the #MeToo movement and has more recently been adopted by a dedicated group of queer people that appreciate its feminist and sapphic potential.

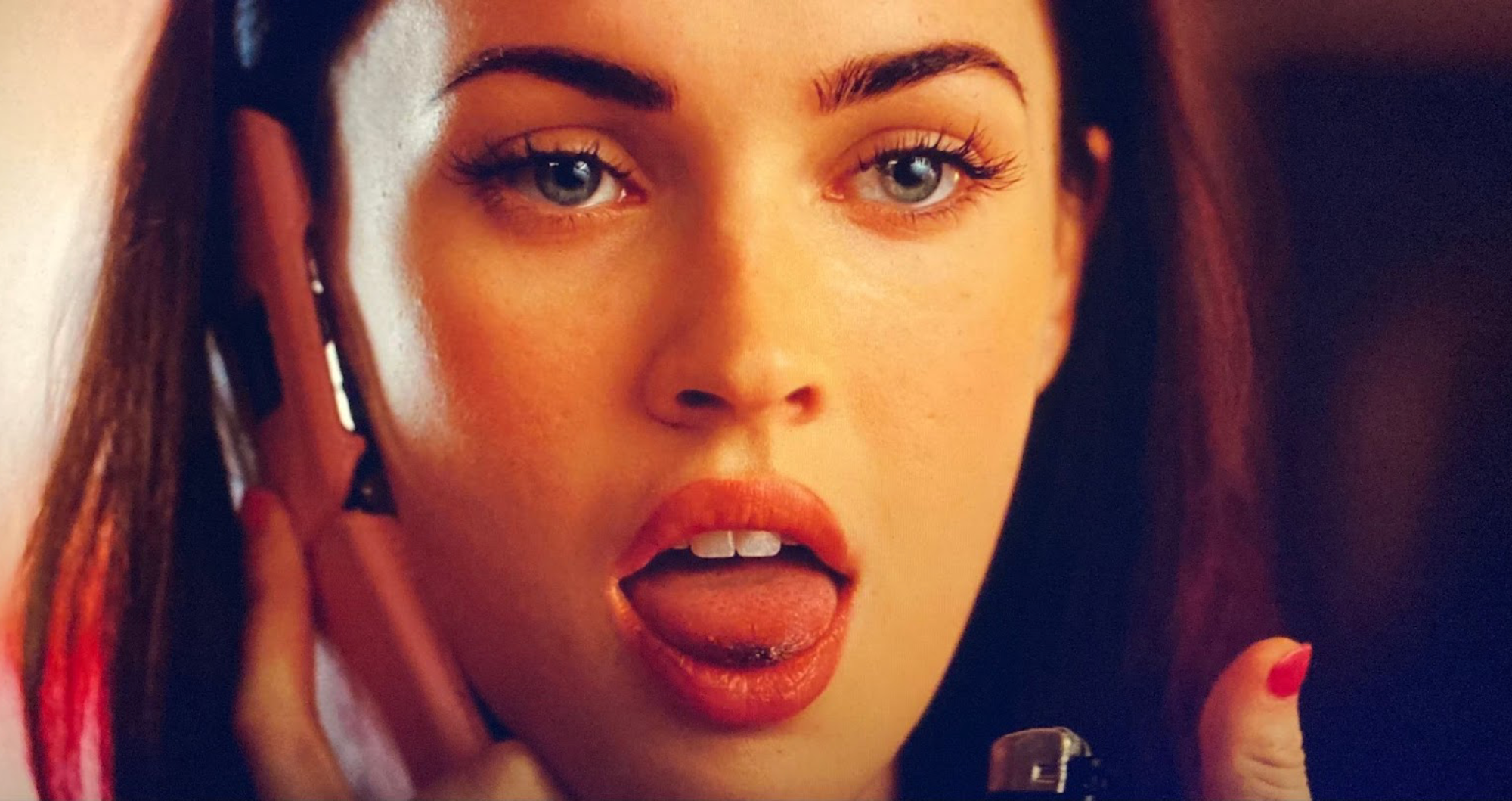

I first encountered Jennifer’s Body on Tik Tok. Creators on the app pitched the story as a cult-status lesbian film that was perfect for a young queer person looking to expand their sapphic movie repertoire. All I knew about the narrative beforehand was that it was a horror-comedy centered around two best friends—Jennifer Check (played by Megan Fox) and Anita “Needy” Lesnicki (played by Amanda Seyfried)—who were supposedly into each other; this was obviously not the extent of the story. The movie’s inciting incident sees Jennifer—a beautiful popular high school girl—dragging her more intellectual friend Needy to their local bar to see the band Low Shoulder. A series of strange events occur during the concert that cause an incoherent Jennifer to leave the bar with Low Shoulder alone. The band attempts to sacrifice Jennifer to Satan to increase their popularity and propel them into fame; however, because they falsely assume Jennifer is a virgin she turns into a succubus—a man-eating demon—instead of dying in the ritual. Jennifer takes her revenge upon the town by seducing and eating boys from her high school. The story primarily features the relationship between Jennifer and Needy, depicting their competitive nature and exploring how growing up has affected them as women and friends. After watching Jennifer’s Body, I was pleasantly surprised by the explicit references to queerness and the inclusion of sapphic moments. I was also shocked by the knowledge that others had watched this film and understood the relationship between Needy and Jennifer to be purely platonic. This notion has bothered me since my first viewing, and it is this need to open previous watchers up to the queer nature and potential of this movie that drives me to write this essay and provide evidence to support this reading of the film.

In “Horror and the Monstrous-Feminine: An Imaginary Abjection,” Barbara Creed argues that horror movies reinforce phallocentric philosophies and seek to solidify the vilification of female bodies. Using the theories of Sigmund Freud, the author establishes that throughout history women’s bodies have been viewed as monstrous due to their lack of phallic genitalia (252); in Jennifer’s Body, this can be seen through Jennifer’s sexual power. Even before Jennifer becomes a succubus it is apparent that she is confident in her body and sexuality, and it is this lack of phallic genitalia that makes her sexuality so volatile. Creed remarks on the consistency within horror to present the female body and its functions as abject—something that is considered disgusting or distasteful (256). Creed notes that the abject is often linked to religious violations, listing: “sexual immorality and perversion; corporeal alteration, decay and death; human sacrifice; murder; the corpse; bodily wastes; the feminine body and incest” (252); much of which can be found in Jennifer’s Body. Jennifer is offered as a human sacrifice and technically murdered by Low Shoulder only to be reanimated as a succubus due to her non-virgin status. In this way, Jennifer’s body takes center stage not only as a means to lure in sexually interested boys but as a resurrected corpse seeking revenge. Throughout the film, Diablo Cody takes that which is abject and makes the viewer see it either through the lens of comedy or as a mechanism of gaining power. One moment exemplifying this is when Jennifer gets stabbed by Chip—Needy’s boyfriend—and her response is “You got a tampon?” After Jennifer has been sacrificed she shows up in Needy’s kitchen and vomits a comical amount of black bile onto the floor; this particular moment and the numerous jokes relating to menstruation remind the viewer that in this space the abject is not horrifying. In this realm, the female body is not gross and for better or worse it is what makes Jennifer powerful; something Jennifer acknowledges before her transformation, demonstrated when Jennifer grabs Needy’s breasts saying: “these things have power.” While Creed does not comment on queerness in the genre in that chapter, her arguments surrounding the female body and the abject are foundational in understanding women’s role in horror. Acknowledging that Jennifer’s character is primarily used to comment on female sexuality makes her non-platonic interactions with Needy more significant. This film seeks to examine how men treat female bodies and recognizing the significance of Jennifer’s body helps one better comprehend that when she uses it to interact with Needy in a sexual way she is breaking not only societal norms but the norms of the genre.

In “Her Body, Himself: Gender in the Slasher Film,” Carol J. Clover describes the characteristics of the Final Girl. The Final Girl is proclaimed to be a female protagonist that survives to the end of a horror movie—unlike her supporting cast—in this case, Needy. Clover claims that the Final Girl is typically androgynous and throughout the story the audience sees them adopt masculinity and give up their femininity to defeat the antagonist (247). Clover argues that the role of the Final Girl is to shift the narrative from the monster to her. While the ideas presented in this work apply to numerous texts, Jennifer’s Body offers a unique challenge to this perspective. In this piece, the antagonist and protagonists are both female and Needy’s journey as a Final Girl is defined by embracing her sexual fluidity and femininity rather than by becoming more masculine. Clover describes what defines a Final Girl, writing: “the gender of the Final Girl is likewise compromised from the outset by her masculine interests, her inevitable sexual reluctance...her apartness from other girls, sometimes her name” (238). First: Needy is not defined by any masculine-adjacent interests. She may come across as more intellectual than other girls but she enjoys what Jennifer and other girls like. Second: it would not be accurate to describe Needy as sexually reluctant. Needy is in a loving committed relationship with her boyfriend and appears eager to have sex with him for the first time. There is no indication she may be having doubts until the actual sex scene which is likely due to the visions she sees of Jennifer committing murder rather than the actual sex. Needy not only becomes more sexually confident with Chip but she ends up sharing a heated makeout with Jennifer showing how she explores her sexuality outside of the confines of heteronormative society. While at the start of the film, Needy can be seen wearing frumpy clothes and glasses—a stark contrast to Jennifer’s sexually charged halter tops and short skirts—the viewer watches her appearance shift as her sexual experience increases. The audience sees gradual changes in Needy’s appearance, starting with a lack of glasses after having sex with Chip and then wearing more revealing clothes and bold makeup after kissing Jennifer.

Fig 2 (right): Needy at the dance wearing a frilly pink dress, trading her glasses for makeup. A still from Kusama’s Jennifer’s Body (1:16:35).

“When the Woman Looks,” by Linda Williams examines the relationship between female characters and horror movie monsters, while also exploring how the female gaze is punished. The author explains that the patriarchal nature of society allows men to look upon women with desire while disapproving when women look back; females are punished for looking to reinforce the notion that they are meant to be looked at and not participate in the act. Williams writes: “the monster’s power is one of sexual difference from the normal male. In this difference he is remarkably like the woman in the eyes of the traumatized male: a biological freak with impossible and threatening appetites that suggest a frightening potency precisely where the normal male would perceive a lack” (567); this is clear in the case of Jennifer’s Body. Jennifer’s sexual power over the teenage male is what makes her different both before and after she turns into a succubus. While Jennifer is certainly insecure, she operates as an empowered sexually active girl and her hypersexual identity is both what draws in and scares the “normal male.” This concept can also be applied to Needy and Jennifer’s relationship as it is this shared desire for one another that marks them as sexually different. As stated before, this movie offers a new premise in which both the monster and Final Girl are female, yet it is vital to recognize that this movie is not only arguing that their role as women make them sexually distinct but also their desire for each other. Jennifer is only considered the monster because her sexual appetite is stronger than Needy’s, even though both have committed acts that portray them as “biological freaks” in a male-dominated heterosexual society. Williams concludes that “the titillating attention given to the expression of women’s desires, is directly proportional to the violence perpetrated against women” (577); it is important to note that Jennifer’s lack of virginity is what causes her to turn into a succubus. Low Shoulder chooses to sacrifice her after being told she is a virgin and if she had been one she would have died. Before the sacrifice, Needy tells Jennifer that the band is only interested in her because they think she is sexually pure to which she responds: “I’m not even a backdoor virgin.” If Jennifer had stayed dead after the ritual she would have avoided having to commit cannibalism to survive, although it is interesting to observe that Jennifer’s transformation into a succubus gives her power. Jennifer recognizes her indestructibility and how her lack of virginity is what kept her alive, claiming: “I am a god.”

The theories of Creed, Clover, and Williams serve as the foundation for examining women within horror and can be used to recognize the sapphic mood of Jennifer’s Body. At the start of the story, it’s clear that Jennifer and Needy are close. They are best friends forever as their necklaces claim and with Needy narrating the audience knows the longevity of this relationship when she states: “sandbox love never dies.” The story does not shy away from using suggestive language to imply the relationship between Jennifer and Needy goes beyond the platonic. Within the first few minutes, Needy can be seen watching Jennifer perform a cheer routine only to be interrupted by another person in the bleachers saying: “You’re totally lesbi-gay.” The interjection of Needy’s narration makes this comment feel almost like the viewer is stopping the scene to point this out. It should be noted that this term would not have been used as a compliment rather as a way of drawing attention to the strange nature of Needy’s interest in Jennifer, altering the audience from the start that they should pay attention to how the two interact and priming them to see the relationship through a queer lens. It is also established that Needy and Jennifer have some kind of psychic connection. Needy is able to sense when Jennifer enters her home and can tell when and where Jennifer kisses Chip at the end of the film. This is another way the audience is clued in on the fact that they should pay close attention to the two girls’ relationship.

Fig 7 (right): Needy gives Jennifer a longing glance after Jennifer reaches for her hand. A still from Kusama’s Jennifer’s Body (16:06).

At the climax of the film, an upset and jealous Jennifer seeks out Chip claiming that Needy has cheated on him with the recently murdered Colin and suggests that Chip should instead go to the dance with her. It is interesting to note that Jennifer makes up a lie about the relationship between Needy and Colin rather than telling Chip the real way that Needy cheated on him by hooking up with Jennifer only a few days prior. In this way, the film is not taking full advantage of the story’s queer potential. Jennifer needs Chip to show interest in her to not only prove to herself that she can get anyone Needy can, but also to take revenge on Chip for taking up Needy’s time and love. It is both a display of the competitiveness of female relationships and queer frustration Jennifer is forced to face for wanting Needy all to herself. Later when Jennifer is stabbed an intriguing bit of dialogue takes place with Needy claiming “thought you only murdered boys” with Jennifer responding “I go both ways” right before she is injured by Chip. The colloquial phrase “I go both ways” is often used to describe people who identify as bisexual and is one of the more explicit examples of Jennifer voicing sexual interest in Needy.

While critics rushed to the internet to write scathing reviews of the 2009 horror-comedy, scholarship on Jennifer’s Body is lacking. Many of the critical sources that directly engage with the movie are from 2009 and as a result, do not acknowledge the sapphic nature of Jennifer and Needy’s relationship. In The Journal of Religion and Film, Joseph Laycock discusses a variety of the movie’s themes such as religion, virginity, and female sexuality. Laycock remarks that the film “presents several interesting twists on popular conceptions of the demonic and its relationship to the feminine,” recognizing that in Jennifer’s Body the demonic “represents female empowerment” (Laycock, 1). While the text is able to point to specific things the movie articulates, its queer potential is not explored to the fullest extent. There is no acknowledgment of the physical and emotional relationship between Jennifer and Needy with Laycock only considering the ill-treatment of Jennifer towards Needy since the start of their friendship. Despite remarking on a wide range of the film’s features it does not even consider its queerness; Eoin Rafferty’s piece in The Irish Journal of Gothic and Horror Studies is no different.

Like Laycock, Rafferty summarizes the film and mentions the representation of the female body. Rafferty is, however, much more interested in the elements of voyeurism, pop culture, and dark humor present throughout the movie. It’s interesting to note the author’s view towards Megan Fox in the statement: “since the ritual required a virgin, and the victim is played by Megan Fox, Jennifer was not killed” (Rafferty, 1). The diction here clearly implies that Megan Fox, not Jennifer, is the obvious non-virgin, displaying how Fox’s reputation contributed to people’s perception of the character. In this work, there is again no analysis of Jennifer and Needy’s relationship besides an acknowledgment of their friendship. Rafferty briefly mentions Jennifer and Needy’s kiss and the moment in the film where the two have sex with boys but still only describes the relationship as a friendship.

As the film evolved and became known for its majority queer cult following the attitude in discourse has changed. In 2020 Derek Deng wrote the article: “Sexism, Megan Fox and the tragic underestimation of ‘Jennifer’s Body,’” which focuses on how the industry’s perception of Fox as a sex-symbol shaped the success and marketing of the dark comedy. Deng does what previous work did not and describes the relationship as an “implicitly queer relationship” (Deng, 1). The author acknowledges the newness in viewing this film as sapphic, stating: “only in recent discourse, however, have people begun to fully realize what the film signifies and what it says about queer womanhood” (Deng, 2). It is important to note that Deng’s piece is not a published peer-reviewed text exemplifying how this topic has yet to make its mark in academic discourse.

Jennifer’s Body scratches the surface of what queer relationships can look like in horror and exploring the sapphic components of Jennifer and Needy’s relationships is not only significant in the study of film theory but also queer studies.

Works Cited

Clover, Carol J. “Her Body, Himself: Gender in the Slasher Film.” Feminist Film Theory: A Reader, by Sue Thornham, Edinburgh University Press, 1999, pp. 234–250.

Cody, Diablo. Jennifer's Body. Twentieth Century Fox, 2009.

Creed, Barbara. “ Horror and the Monstrous-Feminine: An Imaginary Abjection.” The Dread of Difference: Gender and the Horror Film, by Barry Keith Grant, University of Texas Press, 1996, pp. 251–266.

Deng, Derek. “Sexism, Megan Fox and the Tragic Underestimation of 'Jennifer's Body'.” UWIRE Text, 2020, p. 1.

Fonseca, Sarah. “Too Little, Too Late: The Queer Cult Status of 'Jennifer's Body' Is Bittersweet.” Them., Condé Nast, 1 Nov. 2018, https://www.them.us/story/jennifers-body-film-cult-status.

Laycock, Joseph. “Jennifer's Body.” The Journal of Religion and Film, vol. 13, no. 2, 2009.

Rafferty, Eoin. “Jennifer’s Body.” The Irish Journal of Gothic and Horror Studies, 2009, p. 67.

Williams, Linda. “When the Woman Looks.” Re-Vision: Essays in Feminist Film Criticism, by Mary Ann. Doane, Univ. Publ. of America, 1984, pp. 561–577.